More than two hundred years ago Henry Ellis wrote, "All the art of living lies in a fine mingling of letting go and holding on."

I have friends who seem to have this down to an art form. They move on almost effortlessly, with nary a glance backward.

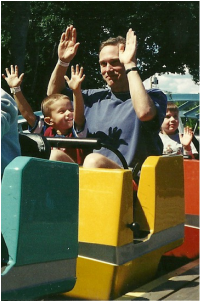

For me, the holding on part has always come easy. The letting go, not as much. Like having to let my mom go. Was it really that I didn't think it was her time yet, or would I have ever been ready to let her go? And I’m probably rationalizing when I tell myself it’s hard to let go of our son because we waited what seemed like forever for him. Like letting go of his thick little paw that first day of preschool. Which happened to land on September 11, 2001 ...

I have friends who seem to have this down to an art form. They move on almost effortlessly, with nary a glance backward.

For me, the holding on part has always come easy. The letting go, not as much. Like having to let my mom go. Was it really that I didn't think it was her time yet, or would I have ever been ready to let her go? And I’m probably rationalizing when I tell myself it’s hard to let go of our son because we waited what seemed like forever for him. Like letting go of his thick little paw that first day of preschool. Which happened to land on September 11, 2001 ...

I diligently follow the strict preschool rule of no electronics before school, only learning the horrific news of what's happening when Mike calls to tell me he's being sent home (he works in the Portland office of the World Trade Center). We need to decide. Should we send Drew to school? Should we tell him what's going on?

I call the school. Yes, bring him to school. The worst thing we can do is alter our first day of school plans. So I take him, but I don't tell him what's going on because I have so little information and what I do have is so scary and he's only three years old for heaven's sake. I muster the courage to leave him there, holding in my grief—on so many levels—until I get home.

And I know I shouldn't have been, but I was unprepared when our teenage son informed me he wouldn't be playing tennis with me anymore. Although I did manage what I thought looked like a real smile with an "I understand." Surely I should have seen this coming. After all, thinking back, I did it too. I recall my big sister Carol's eighth birthday, when our mom said, "Look out the back door to see what your dad's up to.”

My little sis Ally and I ran to the back screen door with Carol and looked out. There was dad, standing by our rusty swing set, proudly displaying a sparkling girl's bicycle with matching turquoise streamers hanging off the handlebars. As the three of us raced out the back door, we did a double take. What was that parked in the shadow of our sister's stunning new bicycle?

I call the school. Yes, bring him to school. The worst thing we can do is alter our first day of school plans. So I take him, but I don't tell him what's going on because I have so little information and what I do have is so scary and he's only three years old for heaven's sake. I muster the courage to leave him there, holding in my grief—on so many levels—until I get home.

And I know I shouldn't have been, but I was unprepared when our teenage son informed me he wouldn't be playing tennis with me anymore. Although I did manage what I thought looked like a real smile with an "I understand." Surely I should have seen this coming. After all, thinking back, I did it too. I recall my big sister Carol's eighth birthday, when our mom said, "Look out the back door to see what your dad's up to.”

My little sis Ally and I ran to the back screen door with Carol and looked out. There was dad, standing by our rusty swing set, proudly displaying a sparkling girl's bicycle with matching turquoise streamers hanging off the handlebars. As the three of us raced out the back door, we did a double take. What was that parked in the shadow of our sister's stunning new bicycle?

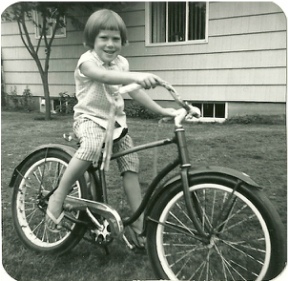

My sister Ally on our beloved bike

My sister Ally on our beloved bike Because there it stood on its trusty kickstand, a small but sturdy, spray-painted, navy blue boy's bike with big fat tires, looking like the unfortunate half-brother of Carol's sleek new bicycle. "Hey, Dad, who's that for? We don't have any boys in our family."

Dad's amused reply: "It's for you and Ally to share. With your big sister learning to ride, we thought you two might want to try it. The guys at the store threw it in for an extra $5. What do you think?"

What did we think? We thought someone must have made a mistake—after all, it wasn't either of our birthdays. Ally and I didn't care that it was a used boy's bike—it had two wheels, a pair of handlebars, and sported multi-colored streamers to boot. The only thing that glorious bike didn't have was training wheels.

No matter, there was a sloped dirt road next to our yard and if I started at the top I could get some momentum going and make it a few yards before crashing. What I needed was someone to hold that seat and give me a little push. I'd beg Mom, Dad, or Carol to hold the seat and I'd take off hollering, "Hold on...hold on..."

When I thought I had my balance, I'd yell, "OK. Let go!" And away I'd go, trying to avoid potholes and rocks as I'd careen into a rosebush in our neighbor's yard at the end of the street. Before long, I had the scrapes, bruises, and bandages to prove I was learning to ride. And I loved it—the sense of freedom and adventure, the ability to travel smoothly and efficiently, the knowledge I could get back home in a hurry whenever I felt like it.

As I thought back to my six year old self, I realized the lessons I learned on that bike are lessons I keep relearning as I travel through life. I now understand how my mom’s bi-polar illness plays a part in my reluctance to let go—my fear of not getting filled up before something changes.

Dad's amused reply: "It's for you and Ally to share. With your big sister learning to ride, we thought you two might want to try it. The guys at the store threw it in for an extra $5. What do you think?"

What did we think? We thought someone must have made a mistake—after all, it wasn't either of our birthdays. Ally and I didn't care that it was a used boy's bike—it had two wheels, a pair of handlebars, and sported multi-colored streamers to boot. The only thing that glorious bike didn't have was training wheels.

No matter, there was a sloped dirt road next to our yard and if I started at the top I could get some momentum going and make it a few yards before crashing. What I needed was someone to hold that seat and give me a little push. I'd beg Mom, Dad, or Carol to hold the seat and I'd take off hollering, "Hold on...hold on..."

When I thought I had my balance, I'd yell, "OK. Let go!" And away I'd go, trying to avoid potholes and rocks as I'd careen into a rosebush in our neighbor's yard at the end of the street. Before long, I had the scrapes, bruises, and bandages to prove I was learning to ride. And I loved it—the sense of freedom and adventure, the ability to travel smoothly and efficiently, the knowledge I could get back home in a hurry whenever I felt like it.

As I thought back to my six year old self, I realized the lessons I learned on that bike are lessons I keep relearning as I travel through life. I now understand how my mom’s bi-polar illness plays a part in my reluctance to let go—my fear of not getting filled up before something changes.

I'm thankful I was able to let go of the angst of our mom's death, while holding onto and cherishing memories of her. And I'm grateful she advised us, "Don't turn me into a saint when I'm gone." So wise of her, because now we remember the whole, imperfect person she was, not someone unapproachable on some pedestal, but someone to be loved for all her humanness.

And when I finally was able to let go of the dream of having a child, we were blessed with a son. I'm thankful I didn't realize then that my most important (and surely most difficult) job as a parent is to let him go.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed